From somebody who has recently become interested in our field, to some of our most seasoned professionals, it has been the subject of confusion and debate. In research articles, business circles, and in the mainstream media, the terms "human factors" and "ergonomics" have been used interchangably, implying that they are essentially one and the same.

However, those who use the term "human factors" primarily to describe their work often deal in more specific subject matter than those who use "ergonomics" to describe themselves. This distinction is so pronounced that the BCPE has two separate designations at the top of their professional accreditation structure, CPE (Certified Professional Ergonomist), and CHFP (Certified Human Factors Professional).

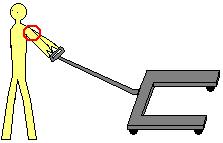

Indeed, those who engage in human factors work tend to concentrate on the cognitive side of the field, and are often involved in the design of controls and complex systems. Alternatively, those who identify themselves as ergonomics professionals often concern themselves with human performance issues (e.g. manual material handling, anthropometric compatibility, awkward posture reduction, etc).

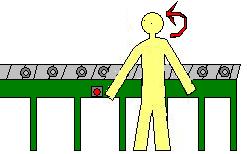

However, to muddy the waters further, there are instances on both sides of the profession where they cross over to the other's specialty, and use that information to flesh out the completion of their respective tasks. For example, a human factors professional will position important controls within 12" of the operator to avoid extended reaching, a design guideline often utilized in physical ergonomic interventions. When consulting operators in the workplace, a ergonomist may recommend the colouring of controls and the moving parts that they control in the same colour. This recommendation, often made by human factors professionals, improves the neurological perception of the operator in relation to the controls that they are supposed to trigger, reducing the learning curve for new employees and overall operator error.

Overall, human factors and ergonomics are the same in definition: the science of studying workplaces in order to improve safety, efficiency, and human performance. The difference in the two terms occurs where definition of work in the field is concerned: the first instances of human factors being implemented in the U.S. occured with the military, where the bulk of work performed concerned the design of complex systems, such as fighter jets. The term stuck wherever work on controls, systems, and human cognition was being conducted, hence its association to this day. Ergonomics came in as a defining term as the profession evolved, as the focus shifted towards human performance, hence its association with physical issues.

In conclusion, this blog will use "ergonomics" to refer to all issues addressed by this blog, as the science of fitting the work to the person should be linked to one term.

We are in the business of making things easier for people, so clearing up confusion ought to be one of our specialities!